Funded by the generous family of Professor Abe Guz – for whom research into breathlessness was so important, the APM created a fellowship role to source, coordinate and collate best practice on breathlessness to enable better care and to enable further research into breathlessness management.

Professor Abraham (“Abe”) Guz (1929-2014) was a distinguished respiratory physician and scientist who made significant contributions to the understanding of breathing control and the sensation of breathlessness. He held professorships at Charing Cross Hospital Medical School and subsequently led the Department of Medicine at the combined Charing Cross and Westminster Medical School, University of London, until his retirement in 1994.

Guz’s early career was marked by academic excellence, culminating in his graduation with highest honours from Charing Cross Hospital Medical School. Following National Service and research fellowships at Harvard University and the Cardiovascular Research Institute (CVRI) in San Francisco, he returned to Charing Cross, where he established a dedicated respiratory medicine unit. His research program encompassed a broad range of topics related to breathing, including the physiological mechanisms underlying exercise hyperpnoea, the neural control of respiration, the influence of airway anaesthesia, and the development of methods for quantifying and managing breathlessness. He also explored pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions for dyspnoea and had a strong interest in palliative care. His commitment to advancing research in this area led him to establish the Breathlessness Research Charitable Trust.

Beyond his work on breathlessness, Guz’s department was at the forefront of research in sleep apnoea, lung cell biology, and the integration of specialist respiratory nurses into community care. He fostered numerous international collaborations, particularly within Europe. He served as Head of the Department of Medicine at Charing Cross and was instrumental in developing innovative teaching methods, including an audio-visual link connecting multiple hospital sites for interactive medical education. Guz’s professional affiliations included active involvement with the Royal College of Physicians and the British Association for Lung Research. Even in retirement, he remained engaged in teaching and research. He is remembered as a pioneering clinician-scientist whose intellectual curiosity, enthusiasm, and dedication to his field left a lasting impact.

What is breathlessness?

- In this resource, we will be using the term “breathlessness” to describe the subjective experience of breathing discomfort that consists of qualitatively distinct sensations that vary in intensity.

- The experience of breathlessness “derives from interactions among multiple physiological, psychological, social, and environmental factors, and may induce secondary physiological and behavioural responses”.

- It is important to define breathlessness is a symptom rather than a clinical sign. It must generally be distinguished from signs that clinicians typically invoke as evidence of respiratory distress, such as tachypnoea, use of accessory muscles, and intercostal retractions.

- Whilst previously thought to be related to hypoxia or work of breathing, subsequent research has demonstrated that breathlessness arises as a complex interaction among multiple physiological, psychological, social, and environmental factors.

- Specific physiological processes may be linked to corresponding sensory descriptors, the best characterized of which are:

- Sensations of work or effort

- Sensory–perceptual mechanisms underlying sensations of work or effort in breathing are similar to those underlying similar sensations in exercising muscle

- Tightness

- Tightness is relatively specific to stimulation of airway receptors in conjunction with bronchoconstriction

- Air hunger/unsatisfied inspiration

- Intensity of air hunger/unsatisfied inspiration is magnified by imbalances among inspiratory drive, efferent activation (outgoing motor command from the brain), and feedback from afferent receptors throughout the respiratory system.[1]

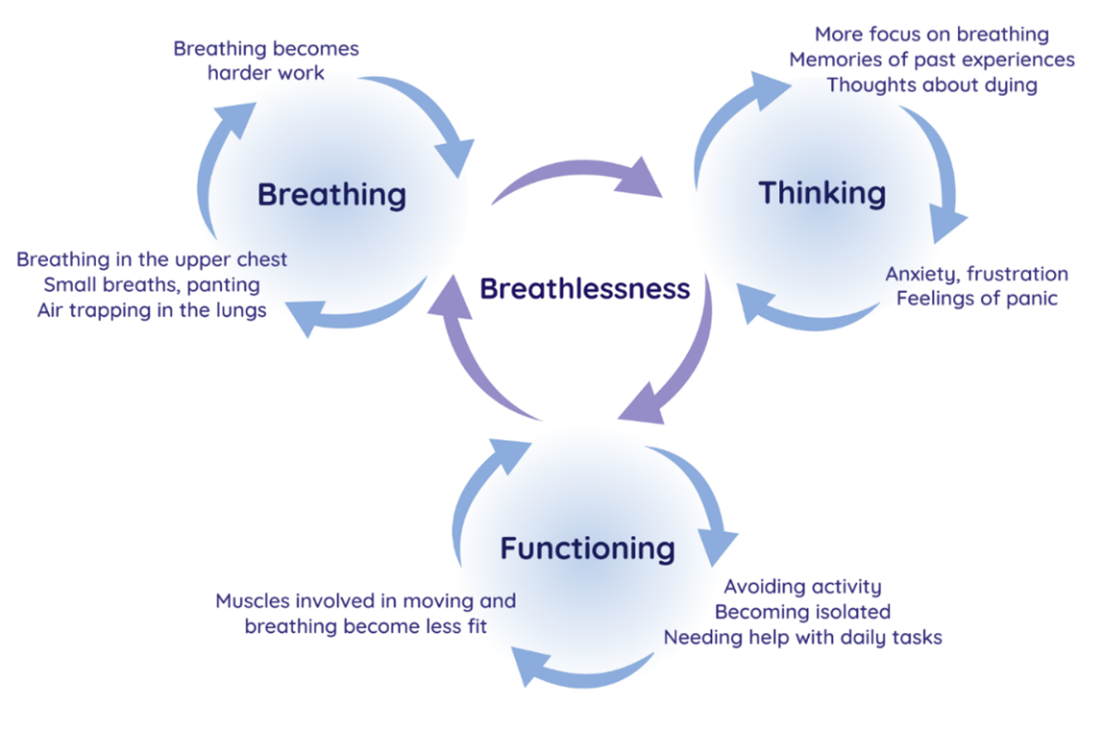

- Understanding breathlessness – the Breathing Thinking Functioning model. Developed by the Cambridge Breathlessness Intervention Service (CBIS) in 2012 as an educational tool for healthcare professionals to explain the mechanisms of worsening symptoms in patients with chronic breathlessness and to aid choice of non-pharmacological interventions with which to help them, this model uses a “vicious flower” maintenance model adapted from cognitive behavioural therapy alongside well-evidenced features in each domain. This model both aims to explain the way in which breathlessness perpetuates and worsens, but also provides a structure and rationale for its management—through aiming to turn vicious cycles into ‘cycles of improvement’.[3]

- Sensations of work or effort

Why is breathlessness important?

- It is estimated that up to a quarter of the general population and half of severely ill patients are affected by breathlessness.[1]

- In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), it has been shown to be a better predictor of mortality than forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1). In patients with heart disease it is a better predictor of mortality than angina. Breathlessness [4] is also associated with decreased functional status and worse psychological health in older individuals living at home.[4]

- Despite its tremendous burden, breathlessness is often underestimated by clinicians. For example, while clinicians reported that less than 30% of patients with lung cancer experienced moderate to severe breathlessness, over 50% of their patients reported the occurrence of this symptom. [5]

- The prevalence of chronic breathlessness is difficult to ascertain, due to studies reporting both acute and chronic breathlessness, but it has been reported to affect between 9% and 59% of the general population. A higher prevalence of chronic breathlessness has been reported in individuals over 70 years of age, with breathlessness in these patients being associated with worsening functional decline and increased five year mortality. Additionally, the aetiology of chronic breathlessness is multifactorial in approximately one third of cases, with common co-existing conditions contributing to symptomatology. [6]

- Five main aetiological categories account for most cases of chronic breathlessness (duration >1 month):

- Pulmonary disease

- Cardiovascular disease

- Respiratory muscle dysfunction

- Psychogenic breathlessness

- Deconditioning/obesity.[7]

- Weighted grand mean prevalence of breathlessness in patients with advanced cancer was 58%; in advanced cancer the prevalence of episodic breathlessness has been recorded at 70.9%. [8]

Measuring breathlessness

- Breathlessness is a subjective experience and thus the gold standard for breathlessness assessment is based on patient self-report.[1]

- Commonly used objective physiological measures such as respiratory rate or oxygen saturations only have a weak association with subjective sensations of breathlessness. In general, lung function tests correlate poorly with the sensation of breathlessness and relatively normal values should not preclude enquiring about breathlessness.

- The European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommends that:

- Breathlessness assessment should include a unidimensional measure of severity, a measure of multi-dimensional functional impact, and patient interview.[9]

- Measures of severity include the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale.

- There are many multi-dimensional measures of breathlessness validated for use in clinical practice – some examples can be found at https://www.thoracic.org/members/assemblies/assemblies/pr/outcome-measures/dyspnea-breathlessness.php

Managing breathlessness

- General approach to breathlessness management:

- Optimise the underlying condition as much as possible

- Could inhaler technique be improved or intensity increased in COPD?

- Could diuresis improve breathlessness in your patient with heart failure?

- Have you considered reversible causes of breathlessness in your patient with cancer – pleural effusions, pulmonary emboli, anaemia?

- Smoking cessation advice in all patients who smoke

- Consider psychological and social impact of the underlying condition – could addressing causes of anxiety improve their symptoms?

- Give brief advice to increase physical activity levels, reassure and encourage: “It’s not harmful to make yourself breathless”, refer patients with lung or heart disease who feel limited by their symptoms for exercise rehabilitation

- Prioritise evidence based non-pharmacological interventions prior to pharmacological interventions

- Optimise the underlying condition as much as possible

- Use the Breathing, Thinking, Functioning model to address patient concerns about their breathlessness:

- Breathing domain

- Dysfunctional breathing patterns are well recognised in breathless individuals without underlying respiratory pathology. Features include apical breathing, higher ratio of inspiratory to expiratory length, absence of end-expiratory pause and frequent sighs or yawns. Breathing pattern disorders occur in about a third of asthma patients, and although there has been no research in other respiratory conditions, such as COPD, there is extensive anecdotal evidence that dysfunctional breathing patterns do occur. Breathless patients experience a sense of ‘needing more air’ and, therefore, may consciously or subconsciously increase their tidal volume or respiratory rate, breathing predominantly using the upper chest and accessory muscles. Apical breathing causes reliance on fatiguable accessory muscles of respiration, underutilising the efficient and relatively fatigue-resistant diaphragmatic muscle, further increasing the work of breathing and intensifying breathlessness.

- Interventions specific to problems with the breathing domain include:

- Breathing Techniques

- Handheld fan use

- Airway Clearance Techniques

- Inspiratory muscle training

- Chest wall vibration

- Non-invasive ventilation

- Thinking domain

- It is well-recognised that the anxiety or fear caused by breathlessness can, in turn, augment the perception of breathlessness. This vicious cycle can lead to a rapidly escalating sense of panic, which most breathless patients experience at some point. The neural processing for this feedback loop is likely to occur in the cortico-limbic areas of the brain, involved in both breathlessness perception and processing of emotion. In addition, anxiety increases the respiratory rate and can cause muscle tension in both the ventilatory pump and other skeletal muscles, so further increasing the work of breathing and respiratory demand.

- Breathing domain

- Interventions specific to problems with the thinking domain include:

-

-

-

- Cognitive behavioural therapy

- Relaxation techniques

- Mindfulness

- Acupuncture

-

- Functioning domain

- As breathlessness is so unpleasant, it is natural to avoid it by reducing activity. However, inactivity leads to muscle deconditioning, with reduced oxidative capacity, muscle fibre atrophy and fibre type shift from type 1 (oxidative) to type IIb (glycolytic) fibres. This increases the demand on the respiratory system and worsens breathlessness further. Patients intuitively understand this ‘deconditioning vicious cycle’, being aware that less ‘fit’ people are more breathless on exertion. Family members and other carers can unwittingly compound the situation, by trying to help through doing activities that the patient might otherwise have done.

- Interventions specific to problems with the functioning domain include:

- Pulmonary rehabilitation

- Activity promotion

- Walking aids

- Pacing

- Neuromuscular electrical stimulation

- Pharmacological interventions

- Pharmacological treatments for the sensation of breathlessness should only be considered once all of the factors above have been considered as the evidence of benefit is limited or disputed and there is evidence of harms. Where evidence supports the use of some medications, this tends to be in patients with severe or terminal breathlessness

- Opioids

- In general are not recommended for patients with non-malignant disease – where used, short acting opioids appeared to be more safe, have potential to lessen dyspnoea and improve exercise endurance, supported benefit in managing episodes of breathlessness and providing prophylactic treatment for exertional dyspnoea.

- In patients already taking opioids for cancer-related pain, the available evidence signals that opioids have a positive effect on breathlessness among opioid-tolerant individuals but overall there is very low quality evidence

- Benzodiazepines

- There is no evidence for or against benzodiazepines for the relief of breathlessness in people with advanced cancer and COPD. Benzodiazepines caused more drowsiness as an adverse effect compared to placebo, but less compared to morphine. Benzodiazepines may be considered as a second- or third-line treatment, when opioids and non-pharmacological measures have failed to control breathlessness.

- Corticosteroids

- Corticosteroids should not be routinely given to unselected patients with cancer for palliation of dyspnoea.

- Antidepressants

- Antidepressants impact on neurotransmitters involved in various brain circuits potentially affecting breathlessness – however despite positive case series, randomised controlled trials have been negative.

- Opioids

- Pharmacological treatments for the sensation of breathlessness should only be considered once all of the factors above have been considered as the evidence of benefit is limited or disputed and there is evidence of harms. Where evidence supports the use of some medications, this tends to be in patients with severe or terminal breathlessness

-

Bibliography

Please click on the links below to be taken to the individual references:

[2] Cambridge Breathlessness Intervention Service. Breathing Thinking Functioning Model

[5] Iyer S, Taylor-Stokes G, Roughley A. Symptom burden and quality of life in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients in France and Germany. Lung Cancer 2013;81:288–93. (Full Text Not Available)

[7] Kuzniar TJ. Assessment of dyspnoea. BMJ Best Practice 2024. (accessed July 15, 2024). (Full Text Not Available)